On February 1, 1865, Abraham Lincoln affixed his signature to the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, completing the final executive step in abolishing slavery throughout the nation. The act itself—quiet, procedural, and almost anticlimactic—belied the enormity of its meaning. With a few strokes of the pen, the federal government formally renounced an institution that had shaped American politics, economics, and social life since the colonial era. Yet the moment was less a triumphant ending than a hinge in history: the legal death of slavery, and the uncertain birth of freedom.

The amendment declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime,” would exist within the United States. Its language was spare, almost austere, reflecting both constitutional tradition and political necessity. By early 1865, the Civil War was clearly tilting toward Union victory, but peace was not yet secured. Confederate armies still fought in the field, and the political future of the South—and of emancipation itself—remained unsettled. Lincoln and congressional Republicans understood that emancipation by executive order, embodied in the Emancipation Proclamation, rested on wartime authority that could be challenged or reversed. Only a constitutional amendment could make freedom permanent.

The path to that amendment had been long and contentious. Slavery had survived earlier compromises and constitutional silences precisely because it was woven so deeply into the nation’s founding. The original Constitution had avoided the word “slavery,” but it protected the institution through clauses on representation, fugitive slaves, and the slave trade. By 1865, that moral and political evasion had become untenable. The war had forced a reckoning, transforming the conflict from a struggle over union into a struggle over the meaning of the republic itself.

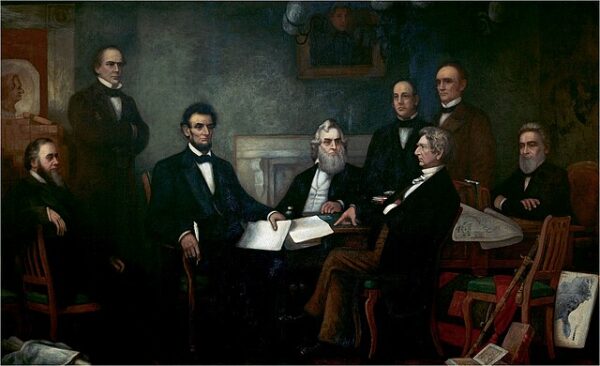

Congress approved the Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865, after a dramatic House vote secured only through intense lobbying, political pressure, and the defection of a small number of Democrats. Lincoln, who had worked quietly but persistently to ensure its passage, signed the amendment the following day—an act not legally required, but symbolically powerful. It underscored the president’s full identification with emancipation and his belief that the amendment represented the moral culmination of the war.

Yet even at the moment of signing, Lincoln understood that abolition was not synonymous with equality. The amendment destroyed slavery as a legal institution, but it did not define citizenship, guarantee civil rights, or protect formerly enslaved people from discrimination and violence. Those battles lay ahead, in Reconstruction amendments, federal legislation, and bitter political struggle. The exception clause—allowing involuntary servitude as punishment for crime—would later become a focal point of criticism, as Southern states exploited it through convict leasing and punitive labor systems that replicated slavery in all but name.

For enslaved African Americans, however, the Thirteenth Amendment marked a watershed. It transformed freedom from a contingent wartime promise into a constitutional fact. Figures like Frederick Douglass recognized its importance while also warning against complacency. Abolition, Douglass argued, was a beginning, not an end. Without political power, education, and legal protection, freedom could be hollow.

Lincoln did not live to see the amendment ratified by the states in December 1865. His assassination in April transformed him into a martyr for union and emancipation, freezing his legacy at the moment of moral triumph. Yet the world he left behind was unresolved, fractured, and contested. The Thirteenth Amendment closed one chapter of American history—the era of legalized human bondage—but it opened another defined by struggle over what freedom would mean in practice.